Peyton Randolph House Historical Report, Block 28 Building 6 Lot 207 & 237Originally entitled: "Peyton Randolph House Block 28 Colonial Lots 207 and 237"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1536

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

PEYTON RANDOLPH HOUSE

Block 28

Colonial Lots 207 and 237

CONTENTS

| Part I. Chain of Title | |

| Maps: | |

| Tyler's Adaptation of the College Map of about 1790 | |

| Bucktrout Map of 1800 | |

| Detail from Frenchman's Map of 1782 | |

| Foundations Uncovered 1938-1940 | |

| Location | 1 |

| History | 1 |

| Part II. Biographical Sketches of Owners, 1724-1783 | |

| Sir John Randolph (1693-1737) | 17 |

| Susannah (Beverley) Randolph (c. 1692-post 1754) | 81 |

| Peyton Randolph (c. 1721-1775) | 85 |

| Betty (Harrison) Randolph (c. 1723-1783) | 141 |

| Appendix | |

| Will of Sir John Randolph | 147 |

| Will of Peyton Randolph | 153 |

| Inventory and Appraisement of the Estate of Peyton Randolph | 155 |

| Will of Mrs. Betty Randolph | 163 |

| Notes from the Humphrey Harwood Ledger B | 167 |

| An Account of Lafayette's Visit, 1824 | 169 |

[ Tyler's Adaptation of the College Map of about 1790]

[ Tyler's Adaptation of the College Map of about 1790]

[Bucktrout Map of 1800]

[Bucktrout Map of 1800]

FROM FRENCHMAN'S MAP1782?

FROM FRENCHMAN'S MAP1782?

PEYTON RANDOLPH HOUSE

LOCATION:

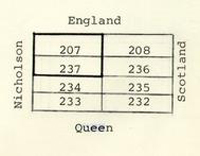

The house known as the Peyton Randolph House is located on the southwest corner of the square bounded by Nicholson, England, Scotland, and Queen streets. It faces Market Square.

The colonial town plan assigning numbers mentioned in deeds has not survived, and Tyler's adaptation of the College Map of about 1790 labels these lots with the names of post-revolutionary owners without distinguishing them by number. The numbers in this diagram, therefore, represent tentative conclusions reached from careful study of the vicinity.

HISTORY:

In the first recorded deed to the property, dated November 11, 1714, the Trustees of the City of Williamsburg conveyed to William Robertson the entire square of eight lots.

This Indenture made the Eleventh day of November in the first Year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord George by the grace of God of Great Brittain, France & Ireland King, Defender of the faith & c and in the Year of our Lord God One Thousand Seven hundred & fourteen Between the Feoffees or Trustees for the Land appropriated for the building & Erecting the City of Wmsburgh of the One part & William Robertson of the County of York of the other part Wittnesseth that the said Feoffees or Trustees for diverse good causes & considerations them thereunto moving but more Especially for & in consideration of five 2 shillings of good & lawfull money of England to them in hand paid at & before the Ensealing & delivery of these Presents, the receipts whereof & themselves therewith fully contented & paid they do hereby acknowledge have granted, bargained, sold, demised & to farm letten unto the said Wm. Robertson his heirs or assigns Eight Certain Lotts of Ground in the said City of Wmsburgh designed in the Platt of the said City by these figures 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 207 & 208 with all Pasturage, Woods & Waters & all manner of Profits, Comoditys & hereditaments whatsoever to the same belonging or in any wise appertaining To have & To hold the said Granted Premises & Every part thereof with the appurtenances unto the said Wm. Robertson his Executors Administrators & Assigns for & during the term & time of one whole Year from the day of the date of these Presents & fully to be Compleated & Ended. Yeilding & Paying to the said Feoffees or Trustees the Yearly rent of one grain of Indian Corn to be paid on the Tenth day of October Yearly if it be demanded, to the intent that the said Wm. Robertson may be in quiet & peaceable possession of the Premisses & that by Vertue hereof & of the Statute for transferring Uses into possession he may be Enabled to Accept a Release of the Reversion & inheritance thereof to him & his heirs for Ever. In Wittness whereof Jno. Clayton Esqr. & Hugh Norvel Gentt Two of the said Feoffees or Trustees have hereunto Sett their hands & Seals the day and Year above written.

Signed, Sealed & Delivered

in presence of

John Clayton [Seale]

Hugh Norvell [Seale]At a Court held for York county15th November 1715 Jno. Clayton Esqr. & Hugh Norvel Gentt Two of the Feoffees or Trustees for the Land appropriated for the building & Erecting the City of Wmsburgh Acknowledged this their Deed of Lease of Eight Lotts or half Acres of the said Land to Wm. Robertson Gentt & on his motion it is admitted to Record

Test Phi: Lightfoot Clk

Truly Recorded

Test Phi: Lightfoot Clk

This Indenture made the Twelfth day of November in the first Year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord George by the grace of God of Great Brittain, France & Ireland King defender of the faith &c and in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven hundred & fourteen Between the Feoffees or Trustees for the Land appropriated 3 for the building & Erecting the City of Wmsburgh of the one part & William Robertson of the County of York of the other part Wittnesseth that whereas the said Wm. Robertson by One Lease to him by the said Feoffees or Trustees bearing date the day before the date of these Presents is in actuall & peaceable possession of Premisses herein after granted to the intent that by Virtue of the said Lease & of the Statute for transferring Uses into possession he may be the better Enabled to accept a Conveyance & Release of the Reversion & inheritance hereof to him & his heirs for Ever the said Feoffees or Trustees for diverse good causes & Considerations them thereunto moving but more Especially for & in consideration of Six pounds of Good & lawfull Money of England to them in hand paid at & before the Ensealing & delivery of these Presents the receipt whereof & themselves therewith fully satisfyed & paid they do hereby Acknowledge have granted, bargained, sold, remissed, released & Confirmed & by these Presents for themselves, their heirs & Successors as far as in them lyes & under the limitations & reservations hereafter mentioned they do grant, bargain, sell, remise, release & Confirm unto the said Wm. Robertson Eight certain Lotts of Ground in the said City of Wmsburgh designed in the Platt of the said City by these figures 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 207, & 208 with all Woods thereon growing or being & all manner of Profits, Comoditys, Emoluments, & Advantages whatsoever to the same belonging or in any wise appertaining To have & To hold the said granted Premisses & Every part thereof with the appurtenances unto the said Wm. Robertson & to his heirs for Ever to be had & held of our Sovereign Lady the Queen in free & Common Soccage, Yeilding & Paying the Quittrents due & legally accustomed to be paid for the Same to the onely use & behoof of him the said Wm. Robertson his heirs & Assigns for Ever under the limitations & reservations hereafter mentioned & not otherwise. That is to say, that if the said Wm. Robertson his heirs or Assigns shall not within the space of Twenty four Months next Ensueing the date of these Presents begin to build & finish upon Each Lott of the said granted Premisses One good Dwelling house or houses of such dimensions & to be placed in such manner as by One Act of Assembly made at the Capitol the 23d day of October 1705 Intituled an Act continuing the Act directing the building the Capitol & City of Wmsburgh &c is directed or as shall be Agreed upon, prescribed & directed by the Directors appointed for the settlement & Encouragement of the City of Wmsburgh pursuant to the trust in them reposed by Virtue of the said Act of Assembly, then it shall & may be lawful to & for the said Feoffees or Trustees & their succesors Feoffees or Trustees for the Land appropriated for the building & Erecting 4 the City of Wmsburgh for the time being into the said granted Premisses & Every part thereof with the appurtenances to Enter & the same to have again as their former Estate to have hold & Enjoy in like manner as they might otherwise have done if these Presents had never been made. In Wittness whereof Jno. Clayton Esqr. & Hugh Norvell Gentt Two of the said Feoffees or Trustees have hereunto sett their hands & Seals the day & year above written.

Signed, Sealed & Delivered

in the presence of

John Clayton [Seale]

Hugh Norvell [Seale]November 12th 1714

Recd. of Wm. Robertson six pounds Current Money being the Consideration within mentioned per me £6:0:0

John ClaytonAt a Court held for York County 15th November 1715 Jno. Clayton Esqr. & Hugh Norvell Gentt Two of the Feoffees or Trustees for the Land appropriated for the building & Erecting the City of Wmsburgh Acknowledged this their Deed of Release of Eight Lotts or half Acres of the said Land to Wm. Robertson Gentt with receipt thereon & on his motion these are admitted to Record.

Truly Recorded Test Phi: Lightfoot Clk

Test Phi: Lightfoot1

Within the next decade the ownership of the eight lots changed as follows:

December 19, 1715. Robertson sold lots 233 and 234 to Philip Ludwell.2 We believe these two lots faced Nicholson Street on the southeastern end of the square.

April 20, 1717. The Trustees gave title to lot 232 to John Tyler, who was at that time "in Actual & peaceable possession."3

5

This lot was apparently the corner lot at Scotland and Queen streets.

January 17, 1718/9. The Trustees gave title to lot 235 to Samuel Cobbs, who was in actual possession.4 This lot apparently adjoined Tyler's on Scotland Street.

December 12, 1723. William Robertson sold the remaining four lots (236, 237, 207, 208) to John Holloway:

7This Indenture made the twelfth day of December in the tenth year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord George by the Grace of God of Great Brittain France & Ireland King Defender of the Faith &c and in the year of our Lord Christ One thousand Seven hundred twenty and three Between William Robertson of the County of York Gent of the one part and John Holloway of the City of Wmsburgh in the same County Esqr. of the other part Witnesseth that the said William Robertson for and in Consideration of the Sum of Eighty pounds Currant money of Virginia to him in hand paid by the said John Holloway before the Ensealing & delivery of these presents the receipt whereof the said William Robertson doth hereby acknowledge and thereof and of every part and parcel thereof doth fully clearly and absolutely acquit exonerate & discharge the said John Holloway his Executors & Administrators by these presents Hath granted bargained and sold aliened & Confirmed & by these presents doth grant bargain sell alien and Confirm unto the said John Holloway and his heirs all those four lots of Ground lying & being in the City of Wmsburgh denoted in the plan of the said City by the figures 236, 237, 207, 208 being the lots whereon the said William Robertson's Windmill stands together with the said Windmill and all Houses buildings Yards Orchards ways Waters profits Easements & Commodities to the said four lots and other the premisses belonging and the Reversion and Reversions remaind & remainders Right & Title Estate claim & demand of him the said William Robertson of in and to the said Lots of Ground and other the above granted premisses and every part and parcell thereof To have & to hold the four lots & Windmill and all and Singular other the premisses herein before mentioned and intended to be hereby granted with their and every of their Appurtenances unto the said John Holloway his heirs and Assigns for ever to the only use and behoof of him said John Holloway his heirs and Assigns forever And the said 6 William Robertson for himself his heirs Executors & Administrators doth covenant grant and agree to and with the said John Holloway his heirs Executors Administrators & Assigns in manner & form following that is to say that he the said William Robertson at the Ensealing and delivery of these presents is and stands lawfully Seized of and in the above granted premisses and every part thereof of a good sure absolute and indefeizable Estate of Inheritance in fee simple And also that he the said John Holloway his heirs & Assigns shall & may peaceably and quietly have hold and enjoy the said granted premisses with the Appurtenances and every part thereof without the lawfull Let Suit Eviction or molestation of him the said William Robertson his heirs or Assigns or any person or persons whatsoever having or claiming or that shal or may have or claim any Estate Right title or Interest from by or under him the said William Robertson his heirs or Assigns or any of them in or to the said granted premisses or any part or parcell thereof and that for any Act or Acts by him the said William Robertson or any other person claiming by from or under him committed done or suffered the said granted premisses and every part thereof now are and for ever hereafter shall remain freed & discharged of and from all other bargains Sales Gifts Grants feofmts. Entails Dowers Mortgages and all other incumbrances whatsoever had made done executed or procured or to be had made done executed or procured by him the said William Robertson his heirs or Assigns or any of them And lastly the said William Robertson for himself and his heirs the said granted premisses with the appurtenances unto the said John Holloway his heirs and Assigns against him the said William Robertson his heirs & Assigns and all other persons whatsoever shal & will warrant and ever defend by these presents In Witness whereof the said William Robertson hath hereunto set his hand & Seal the day & year first above written

William Robertson (Seal)Sealed & Delivered

in the presence of

Wil Toplis

John Randolph

Graves PackAt a Court held for York County Decr. 16th 1723 William Robertson Gent in open Court presented and acknowledged this his deed of sale to John Holloway Esqr. at whose motion it is admitted to record

5

Test Phi Lightfoot Cl Cur

Then on July 20, 1724, Holloway sold to Sir John Randolph one of the four lots acquired six months earlier, apparently the second lot facing Nicholson Street from the corner of Nicholson and England (numbered 237 on the diagram above).

This Indenture made the twentieth day of July in the year of our Lord One thousand Seven hundred and twenty four Between John Holloway of the City of Wmsburgh Esqr of the One part And John Randolph of the Same City Esqr of the other part Witnesseth that the said John Holloway for and in Consideration of the Sum of thirty pounds of lawfull money of Virginia to him by the said John Randolph in hand paid before the Sealing and delivery of these presents the Receipt whereof he doth hereby acknowledge Hath granted bargained and Sold And by these presents doth grant bargain and Sell unto the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns All that Messuage and Lot or half Acre of Land Situate and lying and being in the City of Wmsburgh adjoining to the Lot whereon the said John Randolph now lives which he the said John Holloway lately purchased of William Robertson of the City of Wmsburgh Gent And the Reversion and Reversions Remainder and Remainders thereof and of Every part thereof And all the Estate Right title and Interest of him the said John Holloway in and to the Same and every part thereof To have & to hold the said Tenement and half Acre of Land and all and Singular the premisses with their and every of their appurtenances to him the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns for ever to the only proper use and behoof of him the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns for Ever And the said John Holloway for himself his heirs Extors, and Admtors, doth grant Covenant and agree to and with the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns in manner following that is to Say That he the said John Holloway now at the Sealing & delivery of these presents hath good right and lawfull Authority to Sell and Convey the premisses in manner aforesaid And that the Same shall for Ever hereafter remain unto him the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns freed & discharged of and from all and all manner of former and other Grants Bargains Sales Estates Rights titles troubles and incumbrances whatsoever has made committed done or Suffered or to be had made committed done or Suffered or to be had made committed done and Suffered by the said John Holloway or any other person or persons whatsoever lawfully claiming or to Claim by from or under him And also that the said John Holloway shall and will at any time within the Space of twenty years next Ensueing the date hereof at the proper Costs and Charges of him the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns make Execute & acknowledge such other Conveyance or Conveyances for 8 the better assuring and Conveying the premisses to the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns as by the said Jno Randolph his heirs and Assigns as by the said John Randolph his heirs and Assigns or his or their Councils learned in the law shall be devised advised or required In Witness whereof the parties to these presents first above named their hands and Seals hereunto Interchangeably have Set the day and year first above written.

John Holloway (Seal)Sealed & Delivered

in the Presence of

Phi: LightfootAt a Court held for York County July 20th 1724 John Holloway Esqr in open Court presented & acknowledged this his deed for land lying in Wmsburgh in this County unto John Randolph Esqr at whose motion the Same is admitted to record.

July 20th Recd of John Randolph the Sum of thirty pounds Current money of Virginia the Consideration within mentioned to Jno Holloway At the Court held for York County July 20th 1724 John Holloway Esqr acknowledged in open Court the above receipt which is admitted to record.

6

Test Phi: Lightfoot Cl Cur

The phrase "adjoining to the lot whereon the said John Randolph now lives" raises several questions which are not answered in the York County records and therefore invite speculation. The "messuage" on this lot was doubtless a building Robertson had erected shortly after November, 1714, so that he might retain title to the lot, and Randolph's residence was probably another house on the corner lot 9 (numbered 207 above) which Robertson had built in the same circumstances.

When and how did Randolph acquire title to lot 207? His one other piece of property in the vicinity recorded in York County was lot 174, with a messuage or tenement, "contiguous to the gardens of Mr. Archibald Blair" purchased July 1, 1723, from Alexander Spotswood and sold to Blair July 20, 1724.7 The exact location of lot 174 is uncertain because Blair at this time may have cultivated garden plots west of England Street and/or south of Nicholson. Wherever lot 174 may have been, there is no documentary evidence either for or against the supposition that Randolph at some time lived on it; certainly it cannot possibly be associated with his residence in the summer of 1724. The most reasonable explanation is that Randolph acquired the corner lot, No. 207, shortly after Holloway purchased it in December, 1723, and established his residence there before the following summer; that the deed for this exchange was not recorded in York County; that it may have been recorded in the Hustings Court or in the General Court instead of York for some reason that will never be known unless a contemporary copy should be found in some private collection of manuscripts not yet discovered.

Whatever the details leading to Randolph's purchase of 1724, it is clear that he then owned the two adjoining lots on the western corner of Nicholson and England streets and lived there.

10When he died, March 2, 1736/7, his widow inherited this property for the duration of her life.8 The date of Lady Randolph's death is unknown but may be estimated shortly after 1754.9

By his father's will, Peyton Randolph then inherited the property.10 In practice it was known as "Mr. Attorney's" home as early as 1751, and he may have been living there continuously with his mother.

When Peyton Randolph died, October 22, 1775, his widow inherited the houses and lots.11 Randolph's entire estate was appraised, and this part of it was recorded in York County January 5, 1776.12

Mrs. Betty Randolph lived in the house until her death early in 1783. A record of repairs made during her tenancy is extant.13

Mrs. Randolph's will, probated in the York Court February 17, 1783, ordered the sale of all her possessions "not particularly 11 given away" and the proceeds divided among her legatees.14 Accordingly, the property was advertised for sale:

TO BE SOLD, By public auction, in Williamsburg, on Wednesday the 19th of February next,

The houses and lots of the late Mrs Betty Randolph, deceased, together with a quantity of mahogany furniture, consisting of chairs, tables, mahogany and guilt framed looking glasses, and desks, a handsome carpet, a quantity of glass ware and table china, and a variety of other articles; also kitchen furniture complete. The above mentioned house is two story high, with four rooms on a floor, pleasantly situated on the great square, with every necessary outhouse convenient for a large family, garden and yard well paled in, stables to hold twelve horses, and room for two carriages, with several acres of pasture ground. Twelve months credit will be allowed for all sums above five pounds, on giving bond with approved security, to carry interest from the date if not punctually paid. The EXECUTORS.15

On February 21, 1783, the houses and lots were sold to Joseph Hornsby:

This Indenture made this twenty first day of February in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty three Between Benjamin Harrison the elder, Harrison Randolph, and Benjamin Harrison Junr., Executors of the last Will and Testament of Betty Randolph deceased late of the City of Williamsburg of the one part, and Joseph Hornsby of the County of James City of the other Part. Whereas the said Betty Randolph did by her last Will and Testament bearing date the first day of June in the Year one thousand seven hundred and eighty, among other Things devise her Houses and Lots in the City of Williamsburg (which were devised to her by her late Husband Peyton Randolph) to be sold by her 12 Executors, as by reference being had to the said Wills recorded in the County Court of York will more clearly appear and by virtue of which Devise, the Executors before mentioned did on the [ ] day of February past proceed to sell the same at public Auction after having given notice of such sale, and the said Joseph became the Highest Bidder and Purchaser for the Sum, of Eighteen Hundred and twenty Pounds Current Money.---Now this Indenture Witnesseth, that the said Benjamin Harrison the Elder, Harrison Randolph and Benjamin Harrison junior for and in Consideration of the said Sum of Eighteen hundred Pounds Current Money to them in Hand paid for the Use, mentioned in the said Will, the receipt whereof they do hereby acknowledge and thereof doth acquit and discharge the said Joseph, Hath given, granted bargained, Sold, alien'd Enfeoffed and confirmed, and by these presents doth give, grant, Bargain, Sell Aliene Enfeoff and confirm unto the said Joseph all those Lots or half acres of Land with the Tenements, and appurtenances thereunto belonging, lying and being in the City of Williamsburg whereon the said Betty Randolph lately resided and bounded by the Lots of John Paradise and Lewis Burwell on the East Side by the Street denoted and called [ ] in the plan of the said City and dividing the Tenement of John Blair now in the occupation of James Madison from the said lots on the West by the Street called and known by the Name of Scotland Street on the North and by the Market square on the South side together with six half Acre Lots denoted in the plan of the said City by the figures 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, and 184 which were conveyed to Peyton Randolph by William Robinson and Elizabeth his Wife of the County of King and Queen, and by Peter Randolph of Wilton in the County of Henrico, as by reference being had to the said Indentures will more fully appear and which said Lots were devised to the said Betty Randolph by her deceased Husband, and by the said Testatrix devised to be sold: and the Reversion and Reversions, Remainder and Remainders Rents Issues, Profits and appurtenances whatsoever to the same belonging or appertaining and all the Estate Right, Title, use trust Interest, claims and demand whatsoever of them the said Benjamin Harrison the elder Harrison Randolph and Benjamin Harrison Junior or either of them of in and to the same or to any part thereof, and all Deeds, Evidences, and Writings touching or concerning the same. To have and to hold the said Lots and Tenements with their appurtenances before mentioned to him the said Joseph, his Heirs and assigns to the only 13 proper use and Behoof of him the said Joseph his Heirs and assigns for ever.

In Witness whereof the parties to these presents have hereunto set their Hands and affixed their Seals the day and year above mentioned

Benjamin Harrison (Seal)

Harrison Randolph (Seal)

Benjamin Harrison, Junr. (Seal)Sealed and Delivered

in the Presence of us

Carter B. Harrison

Archibald Denholm

Thomas B. Dawson

David Jameson

William Nelson Junr.At a Court held for York County, the 21st day of July 1783. This Indenture was proved by the Oaths of David Jameson and William Nelson junior

Witnesses thereto and at a Court held for the said County the 18th day of August 1783 the said Indenture was proved by the Oath of Thomas Dawson another Witness thereto and ordered to be Recorded.

16

Teste

William Russell Cl

From Hornsby the houses and lots passed to Thomas G. Peachy, the owner shown on the College Map and also on the Bucktrout Map of 1800. Although there is no deed to this property recorded in York County after 1783, in the first surviving Deed Book of Williamsburg and James City County a transaction on February 24, 1868, reviews its early nineteenth-century history:

This deed made the 24th day of February A. D. 1868 between Richard W. Hansford, of the City of Williamsburg, State of Virginia, of the one part and Charles C. Hansford, of the Said City and State of the other part Witnesseth; that the said Richard W. Hansford doth grant unto the said Charles C. 14 Hansford the following property to Wit: All those lots of land with the houses thereon, in the said City of Williamsburg, Virginia, now held and occupied by the said Richard W. Hansford, conveyed to him by Archibald C. Peachy and Mary L. Wright and James L. C. Griffin, by deeds which were duly recorded in the clerk's office of the Hustings Court of the City aforesaid, bounded on the north by the lands of Robert H. Armistead, west by a Street leading to the courthouse green, South by the Said Green, and East by a lot now owned by said M. L. Wright and J. L. C. Griffin [the Grave Yard on the "Peachy lot" was reserved to said A. C. Peachy, when he sold to said R. W. Hansford] also all the Household and Kitchen furniture of the said Richard W. Hansford.

In trust to indemnify and save harmless William W. Vest, as Surity for the Said Richard W. Hansford to a Single bill under Seal to Robert F. Cole for Thirty Six hundred and fifty eight dollars and thirty seven cents dated 12th July 1859; and also to indemnify and save harmless the said William W. Vest as surity for said Richard W. Hansford to a single bill under Seal to Walker W. Vest and J. B. Cosnahan trustees of R. Lipscombe for Two hundred & thirty Seven dollars and two cents, dated the 28th day of December A. D. 1860; and also to indemnify and save harmless the said William W. Vest in any other debt for which he may be bound as surity for said Richard W. Hansford

And for the further purpose of indemnifying and saving harmless the said William W. Vest as his surity, the said Richard W. Hansford doth assign transfer and set over unto the said Charles C. Hansford as trustee a debt due him by Mary B. Wills for Two thousand dollars with interest from the 1st of January 1862 (for which he holds a single bill) the said debt to be collected by the said trustee Charles C. Hansford when required by the said William W. Vest and the proceeds applied to the payment of the before mentioned or any other debts, for which the Said William W. Vest is bound as Surity for the Said Richard W. Hansford.

Witness the following Signatures & Seals

R. W. Hansford (Seal)

Charles C. Hansford (Seal)In Williamsburg Hustings Court Clerk's Office April 9th 1868

17

This day the foregoing deed of trust Was acknowledged in the office aforesaid by Richard W. Hansford a party thereto to be his act and deed and thereupon admitted to 15 Record. "Four dollars worth U S R Stamps on this deed"

Teste

Wm H. Yerby C

Since Hansford's title was recorded in the Hustings Court, the deeds are not extant. The Williamsburg Land Tax Records, 1782-1861,18 however, furnish hints to changes in ownership, for they contain lists of owners of town property, the total number of lots for which each owner was taxed, the value of his property, and the amount of the tax.

These are the pertinent notes:

| 1784. | Betty Randolph, 3 lots, valued at £6. |

| 1785-1797. | Joseph Hornsby, 5 lots, valued at £10 in 1785 and increasing to £21. |

| 1797. | George Carter, 4 lots, valued at £18. |

| 1798. | George Carter, 9 lots, valued at £110. Joseph Hornsby not listed. |

| 1799. | George Carter, 9 lots, valued at £110. |

| 1800. | Neither Joseph Hornsby, George Carter, nor Thomas G. Peachy listed. |

| 1801-1804. | Thomas G. Peachy, 9 lots, valued at £110. |

| 1805-1809. | Thomas G. Peachy, 13 lots, valued at £120. |

| 1810-1817. | Thomas G. Peachy estate, 13 lots, valued at £120-150. |

| 16 | |

| 1818. | Thomas G. Peachy estate, 12 lots, £120, with 1 lot transferred to Thomas G. Peachy, Jr., with this explanation: "Via Mary M. Peachy, house and lot which she has hitherto occupied as a kitchen, laundry, and quarter for her servants, being north of the west, and of her dwelling house and formerly charged to Thomas Peachy's estate." |

| 1849. | Archibald C. Peachy's first appearance on the list with 1 lot and its buildings valued at $1800, the building alone at $1600, and the note "formerly charged to Thomas G. Peachy." |

| 1850-1856. | Archibald C. Peachy, residing in California, but still listed for the property, now valued at $2200. |

| 1857. | Neither Archibald C. Peachy nor Richard W. Hansford listed. |

| 1858-1861. | Richard W. Hansford, 1 lot with buildings valued at $3300. |

From the Hansford deed of trust, February 24, 1868, the ownership of the property can be traced through deeds and other court records on file at the Williamsburg and James City Courthouse. Copies may be found in the Accounting Department of Colonial Williamsburg. Owners from 1868 to the present time were:

| 1868-1884. | Richard W. Hansford |

| 1884-1893. | Moses R. Harrell |

| 1893-1897. | John Dahn |

| 1897-1920. | E. W. Warburton and Lettie G. Warburton |

| 1920-1921. | Williamsburg Incorporated [land company] |

| 1921-1927. | Mary Proctor Wilson |

| 1927-1938. | Merrill Proctor Ball |

| 1938- | Williamsburg Restoration |

SIR JOHN RANDOLPH (1693-1737)

Sir John Randolph, the only colonial Virginian and the only colonial agent to be honored with knighthood, was the colony's most distinguished lawyer in the first half of the eighteenth century. His sincerity and dependability made him a good friend and public servant; his tact, gaiety, warmth, and good humor made him socially attractive and popular. A legal scholar with interest in history and literature, he collected a notable library of books and manuscripts.

Contemporary opinion of Sir John was expressed in his obituary notice:

...from his very first Appearance at the Bar, he was ranked among the Practitioners of the first Figure and Distinction. His Parts were bright and strong; his Learning extensive and useful....

In the several Relations as a Husband, a Father, a Friend, he was a most extraordinary Example....Sincerity indeed, ran through the whole Course of his Life, with an even and uninterrupted Current; and added no small Beauty and Lustre to his Character, both in Private and Publick....

Altho' he was an excellent Father of a Family, and careful enough of his own private Concerns, yet he was even more attentive to what regarded the Interest of the Publick. His Sufficiency and Integrity, his strict Justice and Impartiality, in the Discharge of his Offices, are above Commendation, and beyond all reasonable Contradiction....[He was] an Assertor of the just Rights and natural Liberties of Mankind; an Enemy of Oppression; a Support to the Distressed; and a Protector of the Poor and indigent, whose Causes he willingly undertook, and whose Fees he constantly remitted, when he thought the Paiment of them would be grievous to themselves or Families. In short, he always pursued the Public Good, as far as his Judgment would carry him....

He had in an eminent Degree ... the Air of a Man of Quality. For there was something very Great and Noble in his Presence 18 and Deportment, which at first sight bespoke and highly became that Dignity and Eminence, which his Merit had obtained him in this Country.1

He was the sixth son of William Randolph of Turkey Island and his wife Mary (Isham) Randolph, founders of the Virginia family. William Randolph was already living in Virginia in 1673, when he succeeded his uncle Henry as clerk of the court of Henrico County. Later public offices included justice and burgess for Henrico, speaker and clerk of the House of Burgesses, attorney general, trustee of the College of William and Mary. Though he was nominated for a seat on the Council, he never became a member.

John was born in 16932 at his father's James River plantation at the lower end of Curle's Neck, the Turkey Island estate purchased in the 1680's. His brothers were William of Turkey Island, Thomas of Tuckahoe, Isham of Dungeness, Richard of Curle's Neck, Edward the sea captain, and Henry, who died in England, unmarried. His sisters were Elizabeth, who married Richard Bland of Jordan's 19 Point, and Mary, who married John Stith.3

John spent his childhood at Turkey Island and received his early education at home, tutored by a Huguenot clergyman, probably one of the settlers at Manakin Town for whose problems the elder Randolph was often consulted by the Virginia Council.4

Then he was a student at the College of William and Mary. Since the early records of the faculty and bursar have been lost, the dates of attendance cannot be exactly determined. Commissary Blair, recommending him to the Bishop of London in 1728, identified him as "one of the earliest Scholars."5 The grammar school opened in 1694, but it is not likely that Randolph attended before 1705, when he was twelve years old. From William Byrd's diary6 we know that the boy was enrolled in 1709 and that 20 he finished his studies in the fall of 1711. On November 5 that year "The College presented their verses to the Governor by the hands of the Commissary and the master." Then Byrd "went to the Governor's to dinner and found there Mr. Commissary and the master of the College and Johnny Randolph as being the first scholar, who at dinner sat on the Governor's right hand."

William Randolph the elder had died that spring,7 and young Johnny remained a favorite of his father's friend and neighbor, and on visits to Westover sought advice and received affectionate guidance. In March of 1712 Byrd encouraged him to apply for the position of usher at the college, but his application was rejected "because there were but 22 boys which was not a number that required an usher."8

In the fall of 1712 Governor Spotswood commissioned Randolph deputy attorney general in the counties of Charles City, Henrico, and Prince George.9 In the document itself Spotswood explained that Attorney General Stevens Thomson had requested the appointment of a deputy because he was unable 21 to attend all criminal trials in these counties, and from the commission it is clear that Randolph was expected to prosecute offenders "unless her said Majesty's Attorney General shall personally attend." The only reason for his choice of Randolph the governor gave was in these words: "the which Courts (I am by her Majesty's Attorney General Informed) you Attend."

Since the commission is unsupported by other documentary evidence,10 we do not know when or where Randolph received the legal training the post implied. His eldest brother William was then clerk of the Henrico Court, but there is no record of his studying law. Their father had been attorney general, but only for a year, 1694, because the appointment was criticized on the ground of his ignorance of the law. If young Johnny read law books at Westover, Byrd did not mention the fact in his diary. He could have studied with some practicing lawyer during the spring and summer of 1712. Even a generation later, when the profession was in better standing and better regulated, formal training required a very short period of concentration; Patrick Henry, for example, was said to have studied only six weeks. No doubt it was already customary for the attorney general to pass on the qualifications of an aspirant to 22 practice in the county courts,11 and certainly Stevens Thomson approved this appointment, if he did not suggest it.12

There is evidence that Randolph did act for Thomson in Henrico. In December of 1713 the court ordered payment of 1000 pounds of tobacco to "John Randolph the Queens Deputy Attorney for Indicting & prosecuting two negros belonging to Capt. Thomas Jefferson condemned for the murder of John Jackson." The trial was held at Varina in a court of Oyer and Terminer, where the Negroes confessed and were executed.13 Because the next volume of the Henrico records is missing, like all the Charles City and Prince George records for this period, we can only assume that Thomson's deputy tried whatever criminals were indicted in these counties during the last two years of the attorney general's life. (Thomson died in February, 1714.) Whether Randolph finished out the year 1714 as deputy for John Clayton we do not know.

23His formal legal studies at the Inns of Court began in the spring of 1715, doubtless with the encouragement of Byrd's example and advice. "John Randolph of Virginia, gent." was admitted to Gray's Inn on May 17, 1715, and on November 25, 1717, he was "called to the Bar by the favour of the Bench"; i.e., for some reason--perhaps the high quality of his work--he was excused from further residence and study.14 Like Byrd,15 he probably made good use of social and literary associations in the years at the Inns of Court and established many of the contacts useful to him later as Virginia agent. After being admitted to the bar, he stayed on in London for several months, enjoying life in the great city. On the morning of February 17, 1717/8, he called on Byrd "to take his leave" and to pick up letters to deliver in Virginia.16

24Immediately upon his return to Virginia in the spring of 1718, Randolph entered the public service as clerk of the House of Burgesses. The circumstances of his appointment he explained publicly nearly two decades later in the pages of the Virginia Gazette, when he was defending himself against a virulent attack on his character. Alexander Spotswood, now a private citizen, had just published a tirade against the House of Burgesses and their Speaker, whom he characterized as "a fawning Creature ... whose Pride and Spleen has made him turn against his Benefactor, who first promoted him in the World." On this occasion Randolph, too, lost his temper and wrote in such anger that his sentence structure reflects his emotional distress:

A Brother of mine, had been Clerk of the House of Burgesses, during the Times of Two Governors, his immediate Predecessors, and he serv'd one Session under him. The Gentleman [Spotswood] had a Scheme in his Head, to raise an Army, and Twenty Thousand Pounds to pay 'em, and to march at the Head of 'em against the Indians. My Brother presum'd to utter some Dislike of the Project, in a private Conversation; which being carried to Court, he dismissed, and another appointed. Then he became a Member of the House of Burgesses; and after several Sessions, having pleas'd him in some Vote, the Gentleman tells him, that he had done him great Wrong, in taking his Office from him; that his Successor did not please him, therefore he should be turn'd out; and desired him to accept of it again. He told him No, he did not want it; but that I was expected every Day from England, and if he would give it to me, he would look upon the Obligation to be the same: I arriv'd, and was appointed, and held the Office Four Sessions under him.1725

The journals of the House of Burgesses explain Randolph's allusions. His eldest brother William of Turkey Island became clerk in 1704 and burgess for Henrico in 1715. When the spring session of the General Assembly opened on April 23, 1718, the burgesses had no clerk. Richard Buckner had been removed from the office because he incurred the displeasure of both the governor and the burgesses in a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don't situation concerning the question whether to print Spotswood's closing address as part of the proceedings of the House. The copy sent to the governor in the usual way did not include it, and Buckner was informed by the clerk of the Council, William Robertson: "...the Governour has ordered me to Send you back the last Sheet of your Journall together with a Copy of his Speech that you may insert it in its proper place...." Buckner thereupon included it, and the burgesses decided his action was "unwarrantable", summoned him to appear before the House under guard, fined him and discharged him.18

On Wednesday, April 23, 1718, Thomas Eldridge was sworn in as the new clerk.19 Then on Monday, April 28, "Thomas Eldridge having resigned his Commission of Clerk of the House of Burgesses and John Randolph having taken the Oathes by Law 26 appointed and Subscribed the Test, was by virtue of a Commission from the hon'ble the Lieut. Governour Sworn Clerk in his Stead and admitted to his place in the House accordingly."20 The clerk's regular duties were to keep the records, supervise the printing of the journals and the acts of the Assembly, and deliver bound copies of the printed laws to the counties, the governor, the speaker, and the secretary. He was responsible, too, for supplying the paper, parchment, and other writing materials for the use of the burgesses. He received a salary of £100 with additional payments for "extraordinary Trouble and Service" from time to time, as when the session was of extraordinary length. Each of the committees had its own clerk chosen by the burgesses without an executive commission. Presumably the clerk of the House could employ deputies as needed but was expected to pay them out of his own funds.

Though the clerk was not a member of the House of Burgesses, he sometimes performed other duties in collaboration with elected burgesses. For example, when the House decided in 1728 to prepare a revised collection of the laws in force in Virginia, the committee chosen to oversee the editing and to contract with William Parks for the printing was made up of three burgesses--Speaker John Holloway, Attorney General John Clayton, Archibald Blair--and two other lawyers--John 27 Randolph, clerk of the House of Burgesses, and William Robertson, clerk of the Council.21

In the summer of 1722 Randolph acted as secretary of the Virginia delegation who went to Albany for a meeting with Iroquois chiefs summoned by Governor William Burnet of New York. The Virginia delegates were Governor Spotswood, Councilor Nathaniel Harrison, Burgess William Robinson, and interpreter Captain Robert Hix.22

While he was clerk of the House of Burgesses, Randolph accepted assignments from the Council. In October of 1722 he and Holloway assisted Clayton in the prosecution of a group of Negroes accused of a treason plot.23 In April of 1726, when Clayton was granted a year's leave of absence to go to England on private business, he engaged Randolph as his substitute, with Council approval.

In June, 1726, the acting attorney general was asked to prepare a report on the health of the president of the Council, Edmund Jenings, who had been absent from meetings of the Council and General Court for two full years but had not resigned. Now 28 the illness of Governor Drysdale made the availability of an acting governor especially urgent, and everyone considered Jenings incapable of attending to any business. Speaker Holloway, his old friend and lawyer, hesitated to make an official statement; he had not seen him for six months because of a rift in relations with the entire Jenings family. Robertson, his lawyer at the time, seemed equally unwilling to speak of his incapacity.

With his customary care for accurate detail, Randolph reported that he had visited Jenings several times, at different times of day, and always found him unforgetful, unable to write or speak more than a few words, unwilling to recognize his incapacity, and that Mrs. Jenings supported her husband's determination to keep his position as president of the Council. The conclusion was definite and clear:

And I am of opinion that his understanding and memory are so impaired by his disease, which I take to be a palsie, that he is not capable of forming any Judgment or collecting his thoughts, if he has any, upon any subject whatsoever; nor do I think he can be made to understand any question concerning the affairs of the Government.The Council decided unanimously to advise Governor Drysdale to suspend Jenings from office, and at the next meeting, in August, Robert Carter presided.25

From August to December, 1727, while Robertson was ill with a broken leg, Randolph acted for him as clerk of the 29 Council and also as clerk of the Vice-Admiralty Court.26 The question whether he might use a deputy in one of his clerkships did not arise: the General Assembly was not in session, and all the Council meetings these months were executive.27

Randolph's activity for Robertson in the Vice-Admiralty Court was not his first appearance in that court. Several years earlier he had been prosecuting attorney in several pirate cases, which he described in the same open letter to Spotswood, reviewing their association from 1718 through 1722:

The next Favour he did me was to make me accept of the Office of King's Advocate, in the Court of Vice-Admiralty, by which I lost several Hundred Pounds; but it was necessary for him. I went thro' many troublesome Prosecutions in that Court, against Piratical Effects; defended him against a Claim of the Proprietors of Carolina, for Effects of great Value, brought by Force from thence; was employ'd to settle a Difference between him and Two Captains of Men of War about these Effects, and drew long Writings between them; and then he set me about devising Reasons and Arguments, to entitle him to one Third, which at last he got; I don't say by any clear Right, but by his usual Perseverence, and disobeying the Orders of the Lords of the Treasury. For all this, and out of upwards of 3000 l. he gave me a little Negro Boy, which I could have bought for 12 l. Virginia Money; and if I don't mistake, he got Twenty odd Piratical Negroes for less. Now I thought, so generous a Benefactor ought to have given me 100 l. at least. Then, when several Courts were to be held for Trial of Pirates, upon which handsome Fees were allowed to the Register, whose Office properly and naturally belong'd to me as Advocate, I was never thought of....2830

This was the period of Spotswood's war on the pirates who preyed on Virginia shipping from their headquarters in the West Indies, the Carolinas, and Spanish Florida.29 Ther were frequent squabbles about the division of the spoils; Randolph probably referred to the argument between Spotswood and the Proprietors of Carolina after Lieut. Robert Maynard captured Blackbeard's ship and brought it to Virginia. The records of the Williamsburg trial of the captured crew do not include the name of the king's advocate; he may well have been Randolph.

Another squabble involved twenty-one Negroes confiscated by Spotswood from Thomas Kennedy, captain of the Calliber Merchant out of Bristol. This slave ship was carrying 190 Negroes when it was taken by the pirate Edward England, who held Kennedy captive for two months and then released him and his ship, giving him twenty-one Negro men "as a Satisfaction for the Damage ... done him." When Kennedy reached Virginia, the governor seized the Negroes for the King's service, he said. Other pirates tried and convicted in Virginia included four who were hanged in 1720, two at Urbanna and two at Gloucester Point.

Randolph's most important assignment for the burgesses 31 was as special agent at court, first in 1728 and again in 1732. The regular Virginia agent in London, called the solicitor of Virginia affairs, represented the governor and Council. He lived in London and negotiated administrative action at court as required, reporting directly to governor and Council. He was paid a sort of retaining fee of £100 a year, with an occasional bonus for special services and reimbursement for special expenses. When the burgesses felt the need for an agent of their own, they chose a Virginian to go to London for a limited time on a specific mission. William Byrd had served them three times in this capacity--in 1702, 1718, and 1721.

Randolph's mission in 1728 was to secure the repeal of a clause in an act of Parliament passed in 1723 which prohibited the importation of tobacco stripped from the stalk. Virginia planters argued that shipping tobacco with leaves still attached to stalks only increased the bulk and so raised freight rates and customs duties, that stripped tobacco carried better, kept better, and sold better. They complained further that processors in England, by mixing stems with the leaf, manufactured an inferior product, which lowered the reputation and market value of all grades of Virginia tobacco and cut down on its consumption, so that much of each year's crop had to be held over in English warehouses and therefore sold on long credit.

For several years the Assembly had been trying to improve 32 the tobacco trade in other ways. To prevent damage during shipment they had made it illegal to gouge hogsheads for samples,30 but the practice did not stop, and sailors continued to steal tobacco from the opened hogsheads and sell it without paying duty. To improve the quality of exported tobacco, the Assembly had limited production to 6,000 plants per tithable31 and prohibited the shipment of inferior North Carolina tobacco through Virginia ports.32 The new governor, William Gooch, then called his first Assembly for February of 1728 expressly to work on the tobacco problem.

Two actions were taken: first, the Virginia law limiting production was extended; then a petition to Parliament for repeal of the objectionable part of their statute of 1723 was prepared, together with an address to the king on the subject. On March 28 John Randolph was chosen "the Agent to solicit the said Address & Petition in behalf of this Country."33 When the session closed two days later, the governor expressed satisfaction with their work and 33 declared: "I shall use my best endeavours effectually to introduce your Address to His Majesty and your Petition to the Parliament of Great Britain ... & agree with you, that you can't place the Affairs which relate to the Interest of this Colony, in better hands than Mr Randolph's, who will shortly go for England."34

Gooch kept his promise with letters to the Duke of Newcastle, Secretary of State, and to the Board of Trade. To Newcastle he wrote:

Your Grace will be attended by a Gentleman of this Country, one Mr. Randolph appointed by the Assembly to bring over an Address to his Majesty and a Petition to the House of Commons for taking off the Prohibition laid by Act of Parliament on the importation of Stemm'd Tobacco, which is represented to be as greatly to the Prejudice of his Majesty's Customs, as it is injurious to the Planters here, a considerable part of whose labour is rend'red useless by it. I am perswaded if nothing else stands in its way, I need use no arguments to induce Your Grace to favour this Representation, where the King's Interest concurs with the benefit of His People. 35

To the Board of Trade he explained that he was sending over copies of the journals and laws of this session, together with other public papers, in a box in the custody of "John Randolph Esqr. the Clerk of the House of Burgesses, who, going 34 to England for the recovery of his health, will be ready to satisfie your Lordships in any Point wherein you may desire to be further informed."36 Knowing that the planters' objection to high freight rates and customs duties would not receive sympathetic attention from the merchants in the Virginia trade or the Commissioners of the Customs, Gooch emphasized another argument to support their plea. To the Board of Trade he reported many conversations with the planters, who agreed that much good tobacco, which would have been shipped home if it could have been stemmed, was thrown away by the owners and then "by their Servants & Slaves made up into bundles and sold at a small price to Sailors, who can have no other view of profit thereby, than the running it without paying Duty."

The address to the king also stressed the losses to the royal revenue:

To the King's Most Excellent Majesty. The humble Address of the Council and Burgesses of Virginia

Most Gracious Soverain.Your Majesty's most dutifull, and loial Subjects the Council and Burgesses of this Your Dominion of Virginia, having experienced the late Act of Parliament; whereby the Importation of Tobacco stript from the Stalk is prohibited, are persuaded, that on the one hand the Industry of the Planter is greatly discouraged, and bad and unmerchantable Tobacco shipped off from hence is increased, while a greater quantity of a better sort of 35 Tobacco is suppressed; And, on the other, Your Majesty's Customs are considerably diminished, and many Frauds in the running such Tobacco are introduced and encouraged. In Consideration whereof we presume in all Humility to apply to Your Sacred Majesty, and at the same time to petition Your Parliament for Relief: And cannot doubt but the Wisdom of Your Majesty and that great Council will suggest such Reasons as will sufficiently prove the Expediency of Repealing that part of the said Act of Parliament; so detrimental to Your Majesty and Your People.

In behalf of the Council

37

Robert Carter

John Holloway

Speaker of the house of Burgesses

The agent arrived in London late in July38 and spent the fall at work on all the varied business he was negotiating for the colony, the college, and private clients. It was not until January 17, 1728/9, that the Board of Trade called him to appear and discuss the proposed repeal of the prohibition against stemming tobacco.39 He had already sent in a letter explaining the planters' point of view and reviewing his own activities in their behalf:

After the letter was read, Randolph appeared in person and the Board informed him "That, if his Proposals were found to be of Advantage to the Tobacco Trade and no Diminution to the Revenue, the Board wou'd give him all the Assistance in their Power."41Your Lordships will observe from the Journals of the last Session of the General Assembly in Virginia, that the Council 36 and Burgesses have drawn up an Address to His Majesty and a Petition to the House of Commons, complaining of [the?] grievous burthen they labour under, in carrying on the tobacco trade, from a clause in a late Act of Parliament prohibiting the Importation of tobacco stript from the Stalk, and appointed me their Agent to Solicit the passing an Act, for their relief. But as I apprehended the greatest objection I should meet with, might be made in respect of the Revenue of Cus[toms] before I troubled your Lordships with the matter, I thought it necessary to lay before the Lords of the Treasury a true state of the case: Which their Lordships were pleased to refer to the Commissioners of the Customs for their Consideration and Opinion: And I Imagine that they after a very deliberate Enquiry, are satisfied that the Revenue has been no ways improved by this Prohibition, So that I flatter myself, I shall obtain the Consent of their Lordships, to bring the matter before the Parliament. Yet I think it my duty to acquaint your Lordps of the Steps I had taken, and at the same time to give you all the Satisfaction I am able, as to the Expediency of removing from so beneficial a Trade, a Mischief, which is insupportable to the People who carry it on both in this Kingdom and Virginia.

My Lords.

The Stript tobacco was by many years Experience found a very Vendible Commodity, as it was most fit for the consumption of this Kingdom and always sold for a higher price, and upon shorter credit, than any other Sort.So that the Planters could subsist by their Industry, and the Merchants here transacted business with more ease and less hazard: But Since they have been compelled by this Act of Parliament to import the Stalk, it is not possible for them to manufacture it properly for the Markets in Great Britain; They are loaded with the duty and Freight of that which is not only of no Value, but depreciates the pure tobacco at least 2d. in every pound. The Tobacconists are under a temptation to manufacture the Stalk and mingle it with the leaf, whereby the whole commodity is adulterated, and of course the consumption of it lessened. And The Merchants are obliged to keep great quantities in their Warehouses, and at last to Sell upon long Credit. In consequence of which the price of the Planters Labour, is fallen below what they are able to bear, And unless they can be relieved they must be driven to a Necessity of Employing themselves more Usefully in Manufactures of Woollen and Linen, as they are not able under their present circumstances to buy what is Necessary 37 for their Cloathing, in this Kingdom.

Upon all which considerations I humbly hope I Shall have the honour of your Lordships

countenance and Assistance in my Application to the Parliament and am with all possible respect

My Lords

Your Lordps

Most obedient and most devoted

humble Servant

John Randolph40

Meanwhile Gooch heard that the mission was being criticized and decided to defend his own position. He informed the Duke of Newcastle:

As soon as I heard from London of the many Objections which are made to the Complaint of the Planters in Virginia sett forth in their Address to his Majesty ... I thought it incumbent on Me to support that Address, by laying before your Grace the true reasons which prevailed with me to encourage it....He estimated that smuggling defrauded the government of about 120,000 guineas a year, for about 8,000 hogsheads (a fifth of the total export) went in without the payment of duty. Furthermore, much of this smuggled tobacco was sold on the Continent and shippers received the standard tax refund when it left England, "so that the trash which does not pay duty gets drawback allowance." If the clause were repealed, "this fifth Part of 38 the Tobacco would be Stemm'd & Sorted in the Country, and sent Home by the fair Trader, and be as good as any for the Market, and that which remained would be fit for nothing but the Dunghill."

To the expected objection in London--that taking out the stalk would decrease the weight and the revenue--he replied that the Virginians would "be able to furnish the same weight without Stalks (not that all or one third of the Tobacco would be stemmed) as they at present do with Stalks.... And I can assure your Grace, from a very strict enquiry, that if all the Tobacco sent home were stript from the Stalk, by which the Quality of the Tobacco would be much mended, & the Consumption made much greater, this Country is able to supply the Markets." Finally he concluded:

All these Arguments summ'd up, plead for a Repeal of the Clause, and their reasons are: that the Consumption will be encreased by the amendment of the Quality; that there will be as many or more hogsheads for the encouragement of Navigation; and above all, that his Majesty's Revenue will be considerably augmented.42

A copy of this letter was sent to the Board of Trade, where it was read on June 3,43 apparently after Randolph had left London, for he was back in Virginia at the end of June.44

39During the next session of the General Assembly, on May 26, 1730, the House of Burgesses:

Governor and Council concurred in the commendation and agreed to the appropriation. 46Resolv'd Nemine Contradicente That the Sum of One thousand Pounds be paid to John Randolph Esqr for defraying his Expenses in Great Britain and his late Voyage thither and returning; And as a Recompence for his faithful and Industrious Application there in the service of this Colony according to the trust reposed in him; Whereby was obtain'd the Repeal of a Clause of an Act of Parliament made in the Ninth Reign of the late King George the first, prohibiting the Importation of Tobacco stript from the Stalk or Stem into Great Britain.

Order'd, That the said Sum of One Thousand Pounds be paid to him out of the Publick Money in the hands of the Treasurer.

Order'd, That the Committee of Propositions and Grievances do carry the said Resolve and Order to the Governor and Council and desire their Concurrence thereto.

Order'd, That Mr Speaker from the Chair do let him know how sensible the House is of his personal Merit and in behalf of the People return him the thanks of this House.

Which Mr Speaker did accordingly.

...

Order'd, That Mr Randolphs Narrative of his proceedings in Negotiating the Affairs of this Colony in England pursuant to the Order of this House in the last Session of Assembly be printed.45

Randolph's mission for the college was equally important and successful. By the royal charter of 1693, President Blair 40 and fourteenseventeen other trustees were given control of all college property and revenues "until the said college should be actually erected, founded and established" with a president, six masters, and about a hundred scholars in schools of theology, philosophy, language, and other arts and sciences. In 1728 these requirements had been met, and it was time to make the transfer. Randolph was chosen to conduct the negotiations and to draft the deed of transfer. Blair explained to the chancellor of the college, the Bishop of London:

The Gentleman who is to deliver this [letter] to your Lordship Mr Randolph is one of the Governours of our College; he was one of the earliest Scholars in it, and has improved himself so well in his Studies, that he is now one of our most eminent Lawyers. By his Acquaintance & interest with General Nicholson he hopes that he can prevail with him to joine in the Transfer of the College. I hope your Lordship will favour him with your best advice and Assistance. He is furnished with Materials, and is very capable of transacting such an affair....47

As it turned out, there were only two of the original trustees alive--Blair himself and Stephen Fouace (rector of Hampton Parish while he was in Virginia, from 1688 to 1702), then living in Chelsea, Middlesex. The transfer was accordingly made on their authority. Randolph apparently used all the information in the "Materials" he took along. The legal document he drafted, covering fourteen folios, first reviewed 41 the history of the college from 1693 to 1728 in exact detail--the origin and condition of each source of revenue, the activities and accomplishments of the trustees. Then in the best of legal verbiage the president and six masters and their successors received control of the "manors, lands, tenements, rents, services, rectories, portions, annuities, pensions, and advowsons of churches, with all other hereditaments, franchises, possessions, goods, chattels, and personal estate aforesaid, or so much thereof as should not be before expended and laid out in erecting the said college, or in the other uses aforesaid." 48

On June 30, 1729, Blair informed the Bishop of London: "Mr Randolph is just arrived, and I hear has brought the transfer." 49 An entry in the faculty journal dated "16 August 1729 Being the Next day after the Transfer of the Said College was compleated," records that the president and masters took oaths of allegiance and fidelity and then decided:

Upon consideration of the great trouble Mr John Randolph has been at in drawing and negotiating the Transferr of the

42 College, both in Virginia and in England It is agreed that over and above his Acct of Disbursements upon that Acct (which we expect) a Present be made him of Fifty Guineas. And the President is desired forthwith to pay the same to him with our thanks for his good Services to the College.50

Again, in the fall of 1732, Randolph went to England for his health and to perform missions for the colony, the college, and private clients. The General Assembly had recently achieved real improvement in the quality of tobacco exported to England with the famous Tobacco Act of 1730 inaugurating the inspection system, which required all tobacco to be shipped in hogsheads officially stamped and closed by inspectors at public ware-houses. Gooch was justifiably proud of his part in setting up the system which was to govern tobacco shipping for the rest of the colonial period.51 From it we date "Gooch prosperity."

Now in the summer of 1732, having done all they could in the colony to improve the tobacco trade, the burgesses decided to "take some Measures" to induce Parliament "to establish some better Methods of Securing and Collecting the Duties upon Tobacco, for preventing the notorious Frauds which 43 have long subsisted, and occasion'd the intolerable Hardships that Trade at present labours under." After debate they decided to ask Parliament "to put Tobacco under an Excise" and appointed a committee to draw up a petition.52 In their opinion an excise tax, paid by the buyer in England, would eliminate smuggling and remove many of the opportunities for fraudulent practices on the part of unscrupulous dealers. Thus the new tax would benefit the planter, the "fair trader," the consumer, the king's revenue, and the tax-paying public.

The Council amended the draft of the petition slightly and then recommended that "His Majesty should be addressed on the subject Matter of the said Petition" and "that Application be made to the Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury, for their Favour and Assistance." Also the councilors "desired to be informed" by the burgesses "of the Manner they propose to have the Petition presented, and negotiated." The burgesses thereupon

Resolved, That John Randolph, Esq: be appointed Agent for this Colony, to negotiate the Affairs of the Colony, in Great-Britain: And that the Sum of Two Thousand Two Hundred Pounds, be paid to him, out of the Money in the Hands of the Treasurer, to defray his Expences; and for a Reward for his Trouble, and the taking so long a Voiage.Within a few days both Council and governor approved the appointment and pay.53 44

As in 1728, Gooch prepared the way for the agent with letters of introduction. He informed the Board of Trade on July 18:

But the most remarkable Step taken in this Session is the Application made to the King and Parliament for changing the Customs on Tobacco into the Nature of an Excise, and their appointment of Mr. John Randolph their Agent for negotiating that Affair. Your Lordships will receive from him a Copy of the Address to His Majesty, and of the Petition to the House of Commons, which contains a full Enumeration of all their Grievances arising as well from the loss of Weights in their Tobacco, the Frauds in the Customs and consequences thereof, as the particular Hardships which they conceive they suffer from the Merchants.

I dont pretend to interpose my Opinion on the several Facts suggested in the Petition, otherwise than as it appears very plain to me that both the King and the Planter run very great risques by the breaking of the Merchants under the present management of that Trade, and that both would be better secured by the method the Assembly propose. And this I hope will be a suficient justification for me to recomend both the Petition and the Gentleman who Negotiates it to your Lordships particular favour. I am the more encouraged to hope your Lordships will be pleased to hear him with acceptance, since I am well assured he will make no progress in this Business, without your Lordships Participation, and the general Approbation of His Majesty's Ministers. 54

Two days later he explained to the Secretary of State, the Duke of Newcastle:

The extream low Price to which Tobacco hath been Reduced for sometime past, and the disinclination shown by the Merchants and Factors to Concur in any Measures projected Here for advancing of value ... this General Assembly to prepare an humble Address to His Majesty and a Petition to the Parliament setting forth the many Frauds and Abuses by which His Majesty has not only been deceived in the payment of his Customs but the Planters greivously Injured

45 by the same Means in their Propertys, and their Commodity brought so low, as that they are hardly able to provide Cloaths for the Slaves that make it....This Address and Petition with a Letter to the Lords of of the Treasury they have Sent by an Agent of their own, Mr. Randolph, who hath the honour to deliver this to your Grace; and as he is a Person of great Integrity and is Employed in a Negotiation intended for the encrease of His Majesty Revenue, at the same time that it is proposed to relieve the People of this Colony, I hope I may with greater Confidence recommend him to your Grace's Favour and Patronage, being well assured how much your Grace has at heart His Majesty's Interest, especially when it may evidently be promoted by the Rules of Justice and common Honesty, without any hardship on the Subject, unless compliance with the Laws be Accounted Such....

I am sensible great Opposition will be made to what is Proposed, not only by all who have made an unjust Gain by defrauding the Crown, but even by Men of better Characters whose private Interests is like to suffer by it; And if I may presume to ask one Favour more without Offence, it is that your Grace will be pleased to permit Mr. Randolph, at such time as your Grace shall Appoint, to explain the present way and management of the Tobacco Trade, and the Measures now proposed for its Amendment; And I am perswaded your Grace will then be at no loss to distinguish by what views the different Partys, that are like to be Opponents, are Acted, and whether they there, or We Here, are contending most for the Public Good.

55

In August he gave Randolph still another letter to deliver. This one, addressed to the Bishop of London, mentioned by name two influential Londoners especially important to the success of the agent's negotiations: the prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, and Alderman Micajah Perry, the leading merchant in the Virginia trade and a powerful member of the House of Commons.

This [is] intended to be delivered to your Lordship by Mr. John Randolph, a Gentleman known by your Lordship, and

46 worthy of all Men's Esteem: He is Sent over by our General Assembly, with their Address to His Majesty, their Petition to the Parliament and a Letter from them to the Lords of the Treasury, to Sollicite, with the Consent of the Ministry, for Relief from many Hardships the People here complain of, occasioned by unfair Traders, who Land their Tobacco without paying the Custom; And they humbly Propose to have it put under an Excise, or into any method, whereby the Frauds may be Prevented and the King's Duty secured....I shall hope for Pardon if I report to your Lordship the ill usage I have lately mett with from Mr. Perry, who, I am told publicly declared at the Treasury, my Intelligence I can depend upon, he would remove me from my Government; when just about the same time, he sends me Word himself, I had certainly been called Home, if he had not gone to Sir Robert and put a Stop to it; And all this my Lord without any Provocation from me for so much ill-nature as there is in the one, or his giving me any reason why so much good-nature was required in the Other. ...And I must repeat it, [I] never deceived Mr. Perry in a single Article, unless by being the Contriver of the Regulation the Trade is now in, by which, `tis to be hoped, the Planters will be rescued out of the Clutches of the Merchants, and freed from Artifices whereby the Produce of their Labour fell into Hucksters hands.

If your Lordship is willing to receive further Information Mr. Randolph will be always ready to wait on your Lordship, and your Lordship may depend upon whatever he shall have the honour to relate.56

When Randolph arrived in London some time in the fall, Walpole was preparing his tax program for the Parliament which would meet early in January, 1733. Merchants and other business interests who expected him to extend the list of excise taxes were already publicizing their opposition in the press. Walpole had pushed through the Parliament of 1732 an excise on salt by threatening a new land tax as the alternative, and the merchants anticipated similar taxes in 47 this year's proposal. Whether Randolph approached Walpole or whether the Prime Minister sought out the Virginia agent we do not know. Walpole's biographers agree that he found Randolph a man after his own heart and the Virginia petition peculiarly apt for his purpose, that he "spent long hours with Randolph, discussing every aspect of his excise scheme; indeed, he saw so much of him that some came to believe that Randolph and not Walpole drew up the bill to excise tobacco."57 We know that the Virginia petition of 1732, like that of 1728, was addressed to Parliament and would normally have been presented in the same manner--through the Board of Trade.58 The absence of any reference to the 1732 petition in the records of the Board of Trade supports the assumption that Randolph by-passed the Board on this occasion and allowed (or persuaded) Walpole to incorporate the tobacco excise in his larger tax bill for direct presentation to Parliament.59

One extant letter of Randolph's, written at the end of December to his client, John Custis, included this brief report 48 on the progress of his public business:

I cannot Expect to be able to return so soon as the April Court, but have no doubt of seeing my Friends early in the summer, either by some ship going to Maryland or other parts of the Continent. Our business will I am told be one of the first of the session, and if we succeed will soon be over; and then I can have no temptation to stay here. I say nothing to you about the price of tobacco, as you will have better Intelligence from your Merchants; only the sweetscented is fallen a half penny a pound by the Conduct of some who move in the lower Orb of Trade: Which will always be the Case, while the Merchants are obliged to bond or pay the duty. And Yet those who complain of this Mischief and openly avow it, to be so, are raving at the Folly and Madness of the Virginians to desire a new regulation. I have a great deal to say upon this subject, but as every day is bringing forth new matter, I will leave it for some other Opportunity....60

The details of Walpole's fight for his tax bill on the floor of the House of Commons are pertinent to Randolph's story. The session opened January 17, 1733, but the excise question was not introduced until March 14, when the Prime Minister submitted resolutions for removing import duties on tobacco and substituting a smaller excise tax. His argument in support of the resolutions was a restatement of the Virginia petition, which was published the same month61 as a pamphlet entitled The Case of the Planters of Tobacco in Virginia, As represented by Themselves; signed by the President of the 49 Council, and Speaker of the House of Burgesses. To which is added, A Vindication Of the said Representation (London: printed for J. Roberts, 1733). Apparently Randolph edited the petition enough to bring it up to date, for it contained a quotation from the True Briton of March 8, but he did not expand its argument. His own extension and explanation appeared separately as the Vindication, pp. 17-64. His forthright attack on the opposition and his passionate defense of the Virginia planter's interests, illustrated in the following selections, make it clear that he had cast his lot with Walpole:

...the Legislature of Virginia... being satisfied that none of the Expedients that have hitherto been fallen upon, have had the good Effect that was expected; and that they had little Reason from the late Conduct of some of their Factors in Great Britain, to hope for a thorough Reformation of Abuses by their Assistance; thought it necessary to lay open their Grievances, and to seek Relief upon a just Representation of their Case, which has lately appeared in Print, and been presented to the Consideration of the Publick.

That undutiful Paper has been long talked of about the Royal Exchange, been branded as the most scandalous and groundless Libel that ever was formed, and unworthy of any Regard or Examination; and has given Occasion to Abundance of Ridicule and Abuse upon the Person who came over to support it, as well from those who know he deserves no such Treatment, as from others who are willing to take every thing for granted that is said on one side of a Question....

It is a Pity some of that publick Spirit which at this Juncture appears so splended among them [the opposition], should never be exerted in Favour of a distressed People, by whom many have lived, and some got Estates; if not to forward one Scheme, to propose some other, in their Opinions more effectual, instead of crying out against all Manner of Relief.

The Remedy now offered to the Wisdom of the Nation, is to substitute some other Security in the Room of Bonds, and